Around 1 year ago, our product-tech team initiated a full rebuild of our software suite.

Among other efforts, this initiative involved the redesign and redevelopment of the 3 legacy applications supporting our whole business, used on a daily basis by both our staff and our customers, and already running in production for more than 2 years at that time. The decision of going through this massive rework was obviously not taken lightly by our team nor by our founders, although it appeared that in our case, that decision just made a lot of sense and its timing could not be any better.

It took us 10 months to finalize and deploy the new versions of our apps. Along the way, we managed to resist a pandemic, deal with lockdown, learn to work 100% remotely, but most importantly, settle on a technical stack, adjust the functional scope of our product, and ultimately define and execute a rollout strategy. When we started communicating about this epic success outside the company, other teams facing similar challenges showed interest in our story, and asked about our “why” and the “how”. That’s what motivated us to write this article, the very first entry of Renovation Man’s product-tech blog, hoping that others would benefit from our successful experience.

We did it because it was the only way to deliver at our full potential

First, let’s share why we had to do it. When dealing with a lot of technical debt, your two main options usually are “refactoring progressively” or “rebuilding from scratch”. Refactoring implies that we intend to improve the existing codebase by reworking parts of it. Whether we change the architecture, switch frameworks or factorize/replace/remove huge chunks of code, the refactoring process supposes that we don’t want to get rid of the technical foundations of our legacy software. This is fine in many cases, especially because building such foundations certainly represented a big investment over time. That’s why it is certainly the less risky option of the two.

But sometimes refactoring is not enough. When our current product-tech team inherited all the company’s legacy software from a previous development team, we experienced technical debt the hard way. We honestly tried to refactor bits and pieces during several months, but in the end we knew that no matter how much we patched the codebase, our velocity was still insignificant compared to what we knew we could achieve. We knew we would never deliver at our full potential this way, even with a lot of refactoring. Productivity was stalling and our motivation started getting affected by it.

During developer hiring interviews, we would try to present our legacy architecture, the technical debt and our maintainability issues to candidates…

During developer hiring interviews, we would try to present our legacy architecture, the technical debt and our maintainability issues to candidates…

This is when it became obvious that our only option was a radical approach: throwing pretty much all the existing codebase away and rebuilding everything from scratch.

We had to demonstrate to our founders why it was necessary

Rebuilding a complete product from scratch involves several risks:

- A new codebase means that there are a lot of features to (re)test before moving into production; many regressions can be introduced when compared to the currently existing applications.

- When choosing a new technical stack, it is always tempting to pick the latest technologies on the radar; while this can make a lot of sense in terms of productivity and developer motivation, the team must also take into account the probable learning curve and ensure the stack fits the real functional needs to avoid useless maintenance and infrastructure costs.

- It will take time and resources to rebuild all the existing features; furthermore, during that time no new features will potentially be delivered by the team, which may impact the company’s overall agility and time-to-market.

- Leading such an initiative for several months requires planning, resource allocation, coordination… it is basically like any other project to be managed and tracked in terms of budget and deadlines, with the same risks involved.

Risks such as those are the reason why IT tasks like refactoring tasks are often postponed by decision-makers, not to mention rewriting everything from scratch.

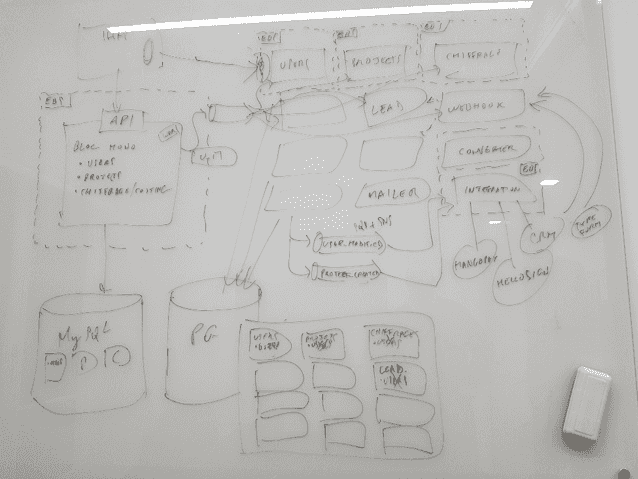

To convince our own founders about the necessity of that extreme option, we demonstrated that it was the only realistic option if we wanted to scale as a startup. We first made a full audit of the existing architecture, code, documentation, tooling, infrastructure, etc. We then presented our conclusions in a non-technical pitch deck: key facts and numbers about our technical debt, risks for the team and the company on the long run, solution comparison, and a plan to get back on track in 6 months with 2 full-time developers (which ended being 4).

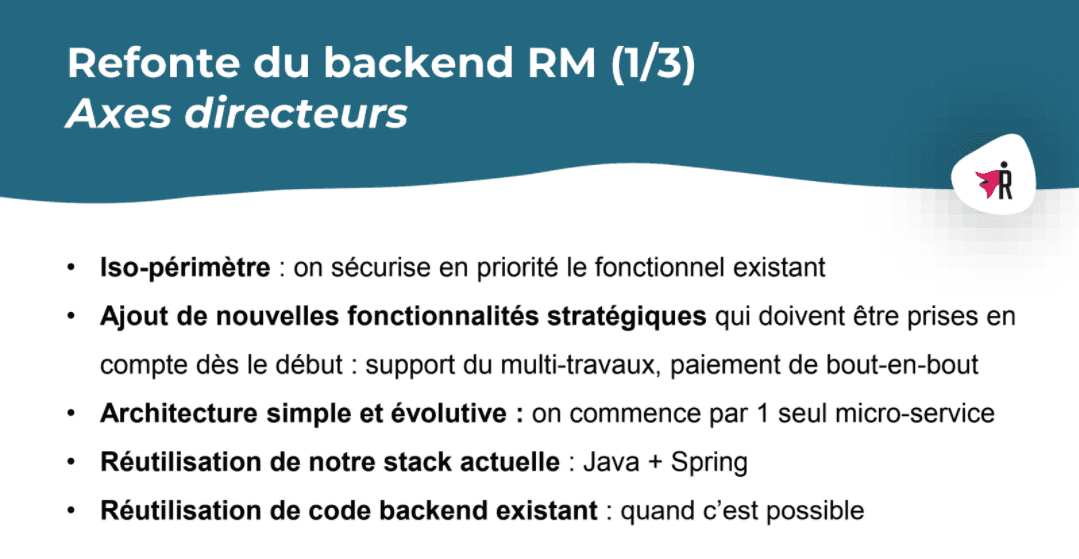

One of the slides of the deck we used to pitch our rebuild project

One of the slides of the deck we used to pitch our rebuild project

We had strong sponsorship, a perfect timing and the right autonomy

Getting the full support of our founders was the first major step in our journey. Every “digital transformation” requires strong sponsorship from the top management, to ensure the teams in charge have whatever they need to succeed, and that everyone across the company is aligned with the strategy. Same goes when rewriting a complete software suite from scratch: everyone should be aware that the initiative is part of the company’s strategy to accelerate operations, that there is a plan which has been discussed and validated, and that it is 100% supported by the top management. As a consequence, the whole company understands the end goal, is supportive, and helps the product-tech team to remain focused on rewriting tasks.

Having such strong sponsorship definitely helped us to prioritize developing our new software, over fixing bugs and improving features in existing production software. But we were also encouraged by the specific context: when the Covid pandemic resulted in a general lockdown in France in late April 2020, it impacted our business by slowing down or delaying renovation projects of many customers. Although our sales team ultimately turned 2020 into a good year, we were able to experience “peace times” (https://svpg.com/product-vs-it-mindset) on multiple occasions, and this allowed us to work on our new software with little disturbance. Retrospectively, although we hope there will never be another year like 2020, it probably represented the perfect moment for our product-tech team to tackle this challenge.

Last but not least, our product-tech team benefitted from a lot of autonomy. We chose the stack, the architecture, the UX/UI, the infrastructure, all according to our high quality standards, and we were able to rely on our seniority to make pragmatic decisions and move fast. We also made most decisions related to the functional scope, as we chose to get rid of features that we believed to be deprecated, and onboarded new ones which were low-hanging fruit in the roadmap. We are able to do so because the people inside the product-tech team had enough knowledge of the business workflows and legacy features, and we could afford to sync with the business stakeholders only on a few occasions. This appeared to be a true game changer, as collaborating with people outside the team represented a lot of constraints at that time, and our autonomy on those matters allowed us to never remain blocked.

We secured the production environment while still releasing pieces of the new software early

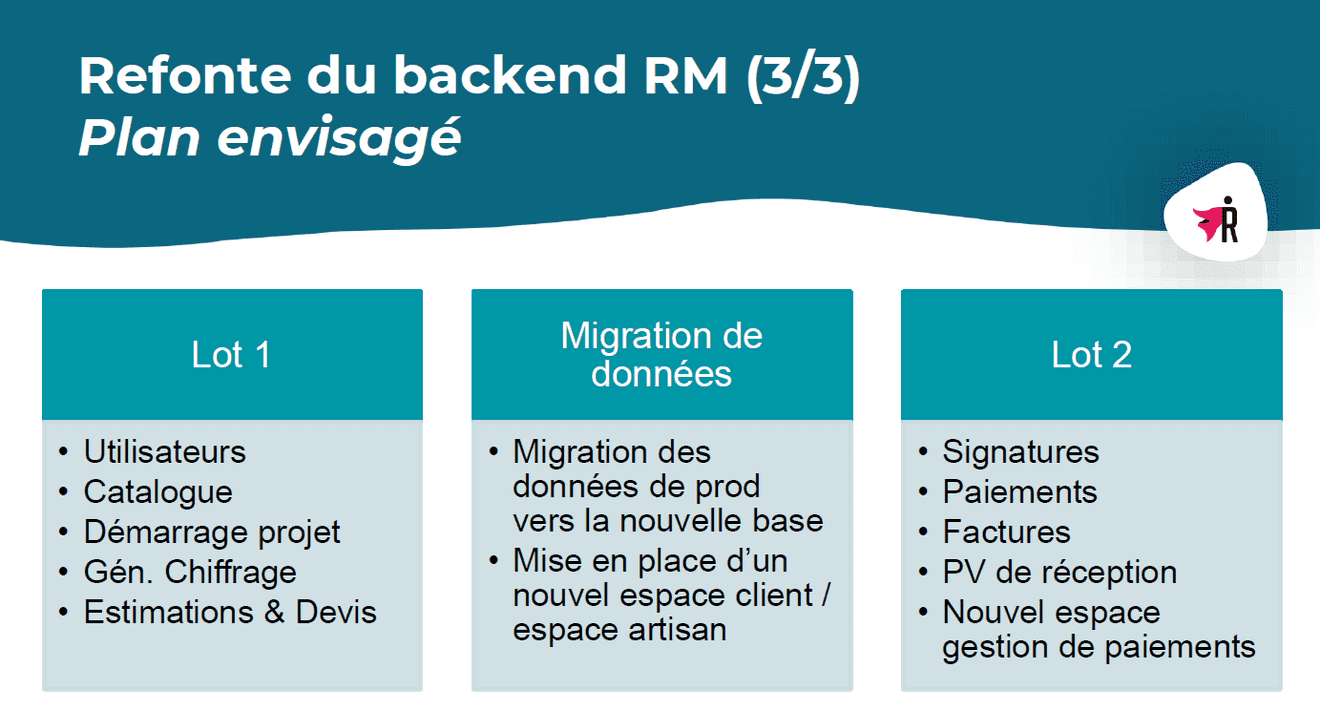

When you are replacing old software, your main concern should be to ensure the continuity of service for your users with at least the same level of quality, which means you need to test a lot before releasing anything in production. On the other hand, you certainly want to avoid the tunnel effect by releasing increments of your new software while still in development. That’s why, in our initial pitch deck to the founders, we suggested rolling out the new software in two phases. Each phase would focus on rewriting an important set of existing features and replacing corresponding parts of the legacy applications in production. Concretely, this meant double-running pieces of old and new software at the same time, while ensuring all our user journeys and business workflows remain operational.

The rollout plan was also part of our pitch deck

The rollout plan was also part of our pitch deck

Having those two rollout phases represented a good trade-off for us, as it made it possible to:

- Avoid spending too much time doing deployments in a complex transitioning environment; because each deployment represented a lot of work if you consider all the automated & manual tests, the data migrations, the decommissioning of old services, the dry runs… it would have required more attention and effort than to just deploy an additional increment in a stable production environment.

- Limit risks related to mixing both legacy and new software in a transitioning double-run architecture; because we were adding communications between components which were not designed to work together initially, and each update to the resulting architecture could end up in unexpected side-effects.

- Focus on rebuilding complex features which required several weeks of design, development and test, without breaking those features in parts; although we have an agile mindset, we believed that it was more important in this context to show polished screens and services to end users; even more to users who are already using similar software and will expect nothing less from a replacement.

There are many rollout strategies in such situations. Probably we could have released in production more than twice, but then again we would have spent more time providing tests, support, monitoring and maintaining our deployments. Our strong sponsorship helped us to focus on rebuilding instead.

What happened next?

We began our journey in May 2020, released part 1 of the new software in November 2020, and then part 2 in March 2021. The whole replacement process took around 10 months instead of the 6 months we originally planned in our presentation to the founders. In-between, a lot happened, some related to the pandemic, and some not, such as scope adjustments that became necessary as we were sharing our work with stakeholders and users, resulting in additional resources being needed. But in the end, no business was lost and users were delighted with the result. More importantly, as expected, the impact of being able to rely on a solid codebase was sudden on our velocity.

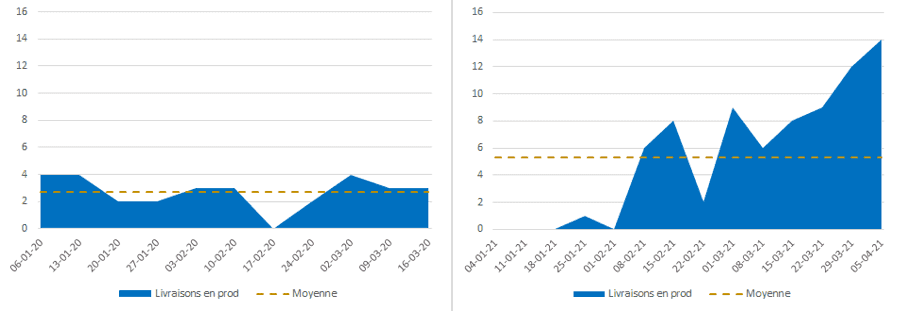

On the left, we see the number of user stories we would deliver in production every week before going through the rebuild in early 2020. On the right, we see how things evolved just after we finalized our rebuild in March 2021.

On the left, we see the number of user stories we would deliver in production every week before going through the rebuild in early 2020. On the right, we see how things evolved just after we finalized our rebuild in March 2021.

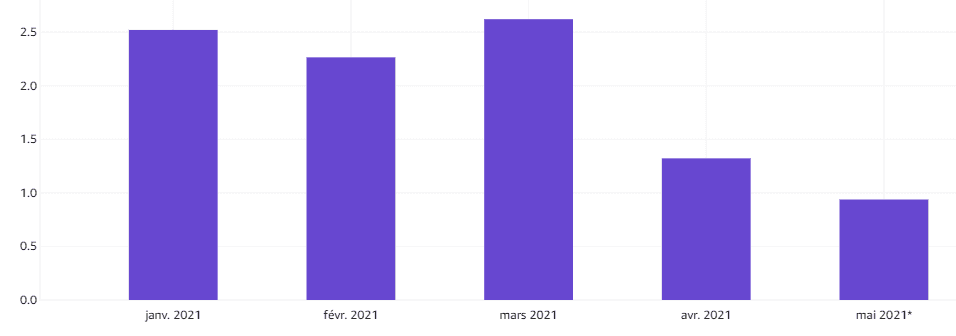

Another positive impact was that by completely redesigning and tailoring the new micro-service architecture to our real needs, our infrastructure costs happened to be divided by more than two.

Although cost reduction was not the primary focus for doing all this, it sure was a nice cherry on the cake.

Although cost reduction was not the primary focus for doing all this, it sure was a nice cherry on the cake.

As you can see, we definitely do not regret betting on this significant effort. After releasing the first part in production, users immediately started to benefit from the new experience and level of support, and things only got better afterwards. In the end, besides velocity and cost reductions, our product-tech team also gained a lot in terms of visibility and legitimacy. This later helped us to get other improvements ideas, on both product and tech topics, approved and supported by the rest of the company.